Throughout history, mankind has sought to alter and enhance the human form, sometimes in the name of beauty, other times, necessity. The evolution of what we now call plastic surgery is a tale interwoven with war, medicine, art, and society’s ever-changing standards of appearance. Far from being a wholly modern invention, the roots of plastic surgery stretch deep into antiquity.

Ancient Beginnings: Reconstructive Roots in Ritual and Restoration

One of the earliest known treatises on surgical repair comes from ancient India. The Sushruta Samhita, a Sanskrit text dated to approximately 600 BC, offers detailed descriptions of nasal reconstruction—a response to punishments that involved the amputation of the nose. This flap technique, in which skin from the forehead was rotated down to form a new nose, is echoed in procedures still practiced in modified form today.

In ancient Egypt and Rome, too, there are whispers of surgical restoration. Papyrus records document wound closure and primitive skin grafting techniques. Roman surgeon Aulus Cornelius Celsus (c. 25 BC – 50 AD) described procedures for repairing ears and lips, which were often damaged in battle or as a result of punishment. These early interventions were functional more than aesthetic, intended to repair rather than refine.

The Medieval Silence and the Islamic Golden Age

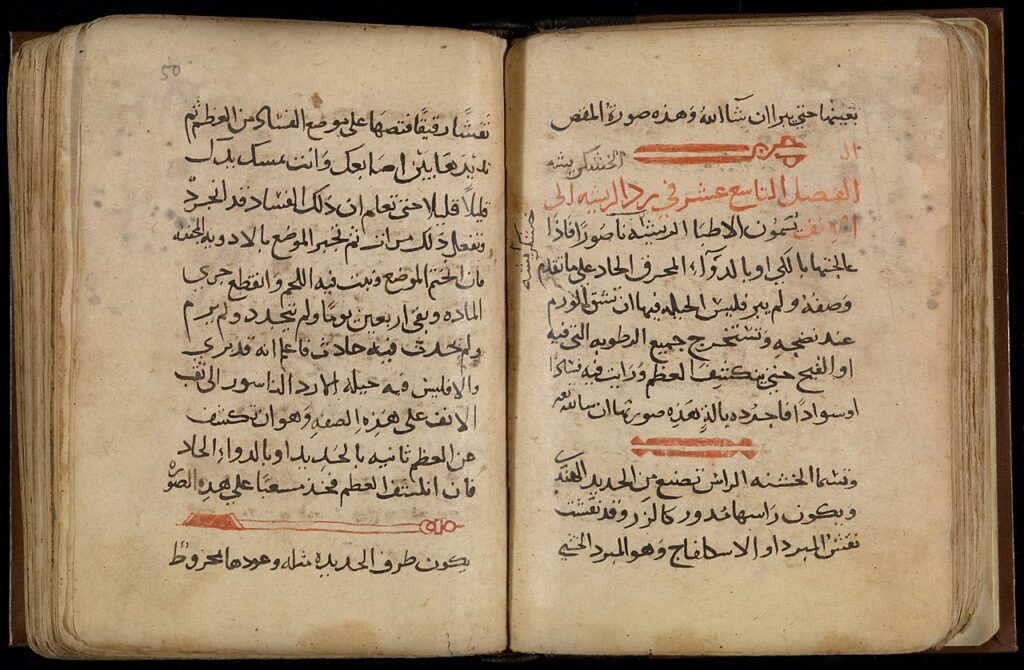

As with many aspects of classical knowledge, the Middle Ages in Europe saw a decline in surgical innovation, hampered by religious doctrine and limited anatomical understanding. However, in the Islamic world, surgical knowledge flourished. Persian physician Al-Zahrawi (Albucasis) in the 10th century CE composed a surgical encyclopedia that detailed various techniques, including cauterization and facial repair.

It is a poignant irony that while the European world recoiled from surgical exploration, the preservation and advancement of ancient methods continued elsewhere, ensuring that the flame of medical progress did not go out.

The Renaissance: Revival and Reimagination

With the dawn of the Renaissance came renewed interest in the human form, not merely in art, but in science. Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical drawings served as both scientific documentation and aesthetic study. Surgery, once the realm of barbers and battlefield butchers, began its slow elevation to a respected profession.

By the 16th century, Gaspare Tagliacozzi of Bologna emerged as a pivotal figure. Often hailed as the father of modern plastic surgery, he developed techniques for nasal reconstruction using skin flaps from the upper arm. His 1597 work De Curtorum Chirurgia per Insitionem detailed both his methods and a philosophical defense of cosmetic surgery: "We restore, repair, and make whole those parts which nature has given, but which fortune has taken away."

The 19th Century: Industrial Perils and Scientific Progress

The Industrial Revolution brought both advancements and accidents. As machines proliferated, so too did injuries, and surgeons were called upon to repair the human body in new ways. Anaesthesia and antisepsis—pioneered by figures like Joseph Lister, transformed surgery from a brutal ordeal to a more controlled, survivable practice.

It was during this century that aesthetic surgery, particularly procedures aimed at facial rejuvenation, began to attract serious interest. Surgeons experimented with methods to smooth wrinkles and lift sagging skin, foreshadowing the development of specific operations such as blepharoplasty for a fresh look. It is a surgical procedure aimed at correcting drooping eyelids to restore a refreshed, youthful appearance. Though techniques remained rudimentary, the seeds of modern cosmetic refinement had been firmly sown.

The World Wars: Necessity and Innovation

The two World Wars were grim accelerants of surgical progress. With faces shattered by shrapnel and flame, a new form of medicine emerged: maxillofacial surgery. Sir Harold Gillies, working in Britain during the First World War, is credited with inventing many of the foundational techniques of modern plastic surgery, including pedicle flap reconstructions that restored not only the visage but often a man’s identity.

His work was continued by his cousin, Archibald McIndoe, who treated pilots during World War II and formed the “Guinea Pig Club,” a community of men who underwent multiple reconstructive procedures. These were not procedures of vanity, but of dignity, efforts to return a face to those who had lost it in battle.

The Post-War Boom: From Stigma to Style

In the post-war decades, as consumer culture blossomed, so too did elective cosmetic surgery. Hollywood played no small role in normalizing aesthetic enhancements. Rumours swirled around movie stars, though few admitted to surgical intervention.

Technological advancements, from silicone implants to safer anaesthesia, made procedures more accessible, while the growing influence of American beauty ideals contributed to the global spread of cosmetic surgery.

The 21st Century: Beauty as Choice, and the Age of the Algorithm

Today, plastic surgery has evolved from a secretive to a celebrated field. Social media influencers openly chronicle their cosmetic journeys. Non-invasive procedures such as Botox, fillers, and thread lifts have transformed the industry, making touch-ups a routine aspect of self-care for many.

Yet, beneath the filters and fluorescence lies a continuity that ties us to our ancient predecessors: a desire to shape the body in the image of our aspirations. Whether in pursuit of beauty, healing, or self-expression, plastic surgery remains a cultural mirror, reflecting not only how we see ourselves but also how we wish to be seen.