By Pauline Weston Thomas for Fashion-Era.com

Seamstresses of 1900 London

- The Edwardian Hostesses in Trade

- Lady Brooke of Eaton Lodge

- Dressmaking as an Edwardian Female Occupation

- The Wages of the Sweat System Dress Trades

- The Report of the Select Committee 1888-1890

- Poor Diets on Edwardian Low Incomes

- Edwardian Department Store Dressmakers

- The Edwardian Corner Dressmaker

- The Edwardian Court Dressmaker of Bond Street

- Edwardian Embellished Blouses

- Poor Income from Blouse Work

- Shawls of Textile Workers

- Glamorous Edwardian Hostesses and Poor Dressmakers

The Edwardian Hostesses in Trade

During the Edwardian era there were few activities in which wealthy ladies could become involved. They became increasingly disinterested in church work and some upper class ladies chose to cultivate a hobby. Retail trade, no matter how flourishing was quite unacceptable in society.

A few society hostesses boldly disregarded convention and busied themselves in the clothing trade. This was out of humanity, not merely boredom. Amongst these ladies Lady Auckland owned a millinery shop; Lady Rachel Byng opened an artistic needlework shop; Lady Duff-Gordon established a fashion house called 'Lucilles' and Lady Brooke ran an underwear shop.

Lady Brooke of Eaton Lodge

Lady Brooke acquired a sewing workroom at Eaton Lodge. She wanted to help alleviate the misery of some delicate village girls. Generally speaking, the life of a seamstress was exhausting and poorly paid, but at Eaton Lodge a fortunate dressmaker would have found good working conditions and an opportunity to develop needlework skills.

The scheme proved to be successful and received Royal patronage. Princess May of Teck who was later called Queen Mary, had her trousseau embroidered at Eaton. As a result it became the vogue to order thin white cambric lingerie from Eaton. It was thought a novel idea that lingerie could be hand stitched at Lady Brooke's residence.

Later Lady Brooke opened a business in Bond Street, but her shop sign, 'Lady Brooke's Depot For The Easton School of Needlework', aroused contempt and mockery. The combination of trade and underclothes was frowned upon in society circles.

For the dressmaker who toiled under her patronage life was very much sweeter than earning a living in other sweat shop establishments.

Dressmaking as an Edwardian Female Occupation

The choice of occupation for the working class girl was limited to either domestic service, prostitution, shop work, the stage or dressmaking. Dressmaking was honest employment and appealed to many. It promised long hours and hard work in every field.

The life of a dressmaker varied according to the place of employment. There were nearly as many different types of dressmaker as there were strata of society. Basically there were five main categories of dressmaker beyond Couturiers like Charles Worth who were a fairly new phenomenon.

Firstly, the high class court dressmakers. Secondly, those who worked in the workrooms of large stores such as Harrods or Peter Robinsons.

Thirdly, the many hands who worked in the East End of London where labour was 'sweated' out of them. Fourthly, the 'little dress-makers' who worked privately in various types of accommodation. Finally, the more or less incompetent dressmakers who were employed almost as an act of charity by private households.

None of these dressmakers was well paid for her labour, although some were employed in more tolerable conditions than others. Their roles were impossible to envy and almost always in complete contrast to the roles played by the edwardian society hostesses.

The more impoverished seamstresses worked to eat, and ate to work, and they were very lucky if they could fulfil even the most basic of human needs.

The different worlds of West End society hostess and East End seamstress were linked by commerce. In the East End one section was devoted to the tailoring trade. Most work was done at home on the sweating system on average for fourteen hours a day.

You are reading an original Edwardian Seamstress article by Pauline Weston Thomas at www.fashion-era.com ©

The Wages Of The Sweat System Dress Trades

The Report of the Select Committee 1888-1890

The East End seamstress could expect to take home a pitifully low wage. In the Report of the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Sweating System 1888-1890, Miss Beatrice Potter (a most famous female Fabian socialist reformer) and others, gave evidence of the atrocious working conditions and meagre pay.

Mrs. Lavinia Casey made shirts at 7 pence a dozen. She normally worked from seven in the morning to eleven p.m. at night. After deducting time devoted to her children she averaged twelve hours work a day.

In that time she normally made two dozen shirts. Her total daily wage amounted to one shilling and two pence. From her weekly earnings she had to deduct two shilling and sixpence for the hire of her Singer sewing machine plus one shilling, to one shilling and three pence for sewing machine oil and sewing thread. She could barely keep her family on this income.

She was in arrears with her payments to the Singer Company, but her livelihood would be threatened if the sewing machine were taken away.

Poor Diets On Edwardian Low Incomes

Like Mrs. Casey, Mrs. Isabella Killick, a trouser finisher, only managed to clear one shilling a day after she deducted the cost of trimmings which she paid for herself. For this she worked some fourteen hours a day, from six a.m. to eight p.m. Her main diet on this wage consisted of a daily herring and a cup of tea. Meat was a food she ate only once every six months.

More rarely it was estimated that a button-hole maker could earn as much as four shillings a day. A Miss Rachel Gashion, an experienced buttonholer often took home a weekly wage of twenty six shillings such was her expertise.

On such low incomes these women were hardly able to afford to eat, and could only dream of wearing the sumptuous clothes that sometimes must have passed through their hands. Most of their clothes were fifth hand and they were often trapped at home because their boots had been pawned for food.

Like other lower class workers, the London seamstress obtained most of her clothes from one of the second hand markets held in London. You can read more about these markets in the section in the history of shopping.

Edwardian Department Store Dressmakers

Working conditions for dressmakers in the larger stores were a little better. After serving a two year apprenticeship to a Court Dressmaker a typical trainee dressmaker received no pay throughout training.

When her training was complete she was offered a weekly wage of two shillings and sixpence. Distressed at the low offer, the seventeen year old trainee dressmaker found a job in a department store workroom in London for seven shillings and sixpence per week. Later she became a chief bodice hand before moving on to another department store and finally marrying.

The wages were obviously not enough because she and her workmates all still lived at home and small economies were essential. To save pennies all the dressmakers from one area travelled to work on an early workman's train. They arrived in London at 8 a.m. and wandered around Covent Garden until work began at 9 a.m., working then until 7.30 p.m.

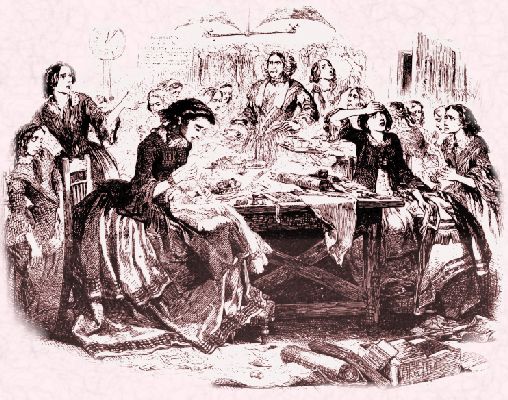

In the department store they wore white overalls and worked at long cloth covered tables. Those who did machine work were called machinists and their job was mainly to stitch linings. Dressmakers worked on made-to-measure dresses doing nearly all the sewing by hand. Only a few dresses were ready-made and these were for window display.

You are reading an original Edwardian Seamstress article by Pauline Weston Thomas at www.fashion-era.com ©

The Edwardian Corner Dressmaker

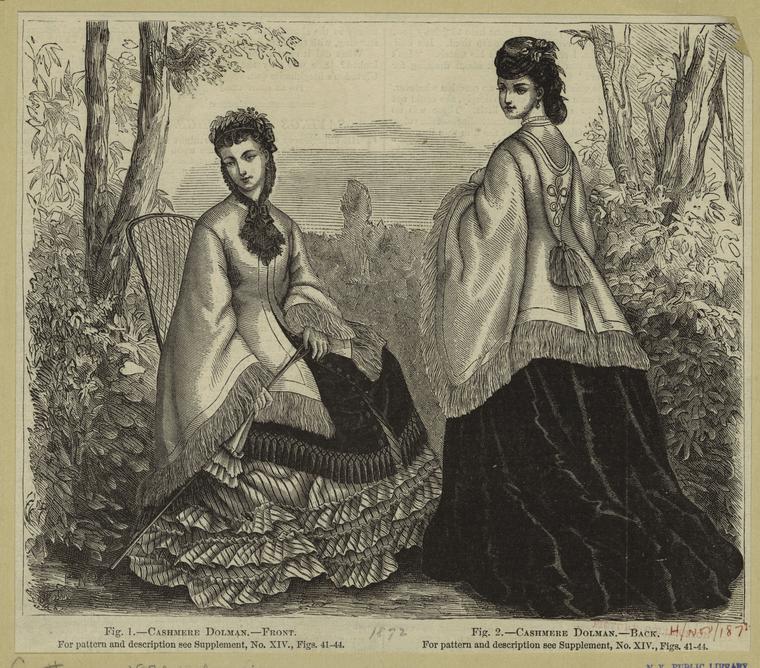

After marriage many women who were fully trained dressmakers would set up as the little dressmaker who could interpret the latest mode at an insignificant price. The answer was to select a dress design from a glossy magazine, then turn to a local dressmaker with a manual Singer sewing machine. The local dressmaker would run up a new gown very cheaply.

Her establishment was likely a room in East London in Bethnal Green where she worked alone. Her client would pay a previously agreed price of between five shillings and five shillings and six pence for the creation.

The Edwardian Court Dressmaker of Bond Street

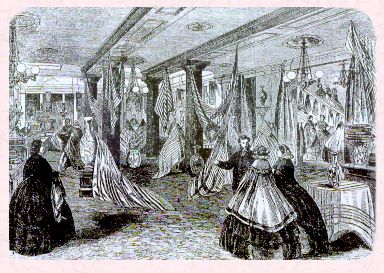

In comparison a Court dressmaker providing a Madame dressmaking service would have charged some eighty guineas for a ball gown. Her clients, of course, would have been offered superior viewing facilities at her mirror filled establishment in Bond Street.

Behind the lavish fitting room the conditions of work for the dressmakers were still very bad. The 'sweated' trade was as prevalent in the West End as the East End.

Because the work had a seasonal nature for months men and women could be unemployed. Then as the season picked up they worked night and day. In the dressmaking and millinery West End trade, English girls were part of the sweated labour. The drawn blinds and work-rooms appeared closed for the day so that dressmakers could work on long beyond the hours allowed by the Factory Acts during the society season.

Edwardian Embellished Blouses

Many dressmakers in such establishments were employed solely to work on blouses. With its profusion of lace and intricate details the blouse was a perfect example of conspicuous waste and conspicuous consumption.

Usually the principal fabrics of the blouse were net and lace, cleverly pieced together with faggotting and lace insertions. This was then further trimmed with satin strappings and velvet ribbons.

After 1905 cotton net was sometimes embroidered with small designs of leaves, flowers or spots and since the blouse was so fashionable, machine embroidery both commercial and domestic flourished until 1914.

Descriptions of blouses in magazines such as Chic Parisian (1905) indicate the degree of ornamentation in vogue at the time for example:- 'Fig. 4029 - Evening blouse of white silk with black silk dots and strips (sic). White maline lace and application of black chantilly lace form the trimming.' You can see some lovely examples of blouses as shown in The Ladies Realm in the Page called Edwardian Pictures.

Poor Income From Blouse Work

The picture of the East End seamstress is perhaps the saddest of all. Working at beautiful blouses elaborately tucked, trimmed, lace embellished and finely gathered into bands, she served to emphasise the two extremes in the life-styles of Edwardian England.

For this poor woman, life must often have seemed one long drudge. It may seem surprising to us today that the majority so meekly accepted Edwardian working conditions with little or no protest.

The retail price of a blouse garment would have been from eighteen to twenty-five shillings, but the maker would get only ten shillings for the whole week despite making more than a dozen intricate blouses.

The maker, a skilled young woman could not make two fine tucked and lace insertion blouses in a day. At ten pence a garment blouse work, was more poorly paid than standard dressmaking despite the skilled sewing expertise needed.

You are reading an original Edwardian Seamstress article by Pauline Weston Thomas at www.fashion-era.com ©

Shawls Of Textile Workers

Photographs of East End seamstresses display a certain uniformity in their personal attire. Their clothes have a wilted, crumpled, droopy look as shown in the header. Their costume invariably consists of a plain skirt and a limp pouched blouse with sleeves pushed up to the elbows as they press on with their hard work. The workers pictured probably worked from home as a team.

Many dressmakers arrived at work wearing a bonnet and shawl and this appears to be a traditional form of dress among lower class textile workers. Beatrice Potter describes their arrival at an East End sweat shop:-

'Some thirty women and girls are crowding in. The first arrivals hang bonnets and shawls on the scanty supply of nails jotted here and there along the wooden partition.

The shawls were sometimes paisley ones, the fashion for these having died amongst the upper classes as the shawls became widely available to the masses.

J. B. Priestley also recalls the textile girls in '...their clogs and shawls' arriving for work some two hundred miles North of London.'

The Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871) marked the end of the shawl as a covetable fashion. In the same way that the Pashmina was cast aside in the late 1990s (albeit frequently retrieved when no other cover up would suit), the abandonment of the Paisley shawl by Edwardian upper class circles was due to its popularity among the lower classes.

By 1870 a Jacquard woven Paisley shawl could be bought for £1, and the identical printed cotton version for mere shillings. The previously exotic, exclusive and rare Kashmir Shawls style beloved since the Regency, became vulgar and everyday as a result of its popularity.

Left - Victorian shawl emporium.

Glamorous Edwardian Hostesses And Poor Dressmakers

A hostess's life was not in fact one of freedom, but rather one of formal leisure highlighted by moments of sexual intrigue. It contrasts vividly with the life of the impoverished Edwardian dressmaker who was actually responsible for producing the lavish gowns that projected the image of her wealthy patron.

Her every waking hour was devoted to activities that barely kept her fed and clothed. The dressmaker is a significant representative of the Edwardian poor, whose sweated labour was essential to maintain the image presented by high society.

If the First World War would change society life it could just as easily change the rôle of the Edwardian dressmaker. History has proved the downtrodden dressmakers of the Edwardian era soon moved on to pastures new.

The munitions factories beckoned. Few chose to relinquish their new found freedom when the Great War ended. Fewer still would be prepared to toil away their lives for a minority who thought the golden age could begin anew and be revived in all its former glory.

You have been reading an original Edwardian Seamstress article by Pauline Weston Thomas at www.fashion-era.com ©

Overall, lower-class fashion in 1912 was marked by simplicity, practicality, and affordability. Clothes were designed to be worn for a long time and were often handed down from one family member to another. While fashion was not a priority for many lower-income people at this time, they still found ways to express themselves through their clothing choices, often by adding small personal touches or adapting their garments to fit their individual needs.

Page date 2001.

Footnote :- This page was partially based on content I updated from a dissertation I first wrote in 1979. The dissertation a Comparative Study Between the Rôles of the Edwardian Hostess and the Edwardian Seamstress looked at the symbolism behind Edwardian dress and the rôles of women in Edwardian society.

In particular it examined the rôle and high lifestyle of Edwardian society hostesses compared with the degrading working conditions and impoverished lifestyle of the seamstresses that made clothes for hostesses.